How Danish agriculture can become a driving force for the green transition

The agricultural sector is facing a paradigm shift. Danish high-tech agriculture can show the world how a pervasive transformation of the industry can reform food production and, at the same time, tackle the crises facing the world. The transformation is all down to something as basic as what we grow on fields, and we may have to get used to the sight of green fields instead of yellow in late summer.

For centuries, we have refined our agricultural production. But even modern Danish agriculture cannot provide sustainable food production, given the imminent climate crisis, the biodiversity crisis and global overpopulation. In short, we have to produce more food on a smaller area. And the production needs to be sustainable.

Those are the words from a number of distinguished researchers from Aarhus University, who all work with future smart and sustainable agriculture and its necessary technologies.

The vast majority of cultivated land in Denmark is used to produce animal feed. But what if we could get a lot more meat out of a much smaller area? And what if this were not the only thing we could get out of the crops?

The future of agriculture is not just about self-driving tractors, autonomous robots, smart sensors, artificial intelligence or other such high-tech solutions.

For centuries, we have cultivated the land in a way that causes environmental issues. Now, Danish agriculture has the opportunity to take the lead and initiate a pervasive green transformation of all of society.

And it all comes down to what we grow on fields and what we put in our mouths.

- ALSO READ: Climate-friendly agriculture requires lots of technology (in Danish)

The fossil infrastructure

Eight kilometres east of Viborg rests the small village of Foulum. The AU Foulum Research Centre is located just outside the village. It is one large, cohesive laboratory ecosystem in which technology and engineering sciences merge with the latest livestock and agricultural research.

The goal is a green revolution. And it is already being tested on fields today.

(Article continues below the video)

AU Foulum has a total of 120,000 square metres of laboratories used by researchers from many different departments at the university.

The focal point for engineering researchers is a green transition of society's current linear fossil economy to a completely new type of economy: A sustainable system based on the premise that we only have the world's biological resources on loan, and therefore they have to be part of a circular system with minimal depletion.

In short: a circular bioeconomy.

"Our entire society is currently chiefly based on fossil raw materials and energy sources. We aren’t just talking about energy for heating, electricity for light and fuel for transport; we’re also talking about how our entire industry and production focuses on predominantly fossil raw materials. If we are to make a difference in climate change and global pollution of nature and the environment, we have to rethink the entire infrastructure," says Professor Uffe Jørgensen, who is head of the Aarhus University Centre for Circular Bioeconomy, CBIO.

Yellow and green crops

What Uffe is talking about basically comes down to what crops we grow on our fields.

For thousands of years, Danish farmers have refined the agricultural sector towards so-called yellow crops. These are annual crops such as cereals and rapeseed, which are green in the spring, yellow in the summer and harvested in late summer so that the fields are brown in the autumn.

“Seen from a circular and resource-efficient perspective, this is absolutely ridiculous,” says Uffe Jørgensen. “We waste up to half of our growing season with no photosynthesis, and what’s worse is that these cultivation concepts exacerbate the sector's serious environmental problems, including nitrate leaching, pesticides and reduced carbon content in the soil. By using green, perennial crops, we can solve many of agriculture’s environmental challenges."

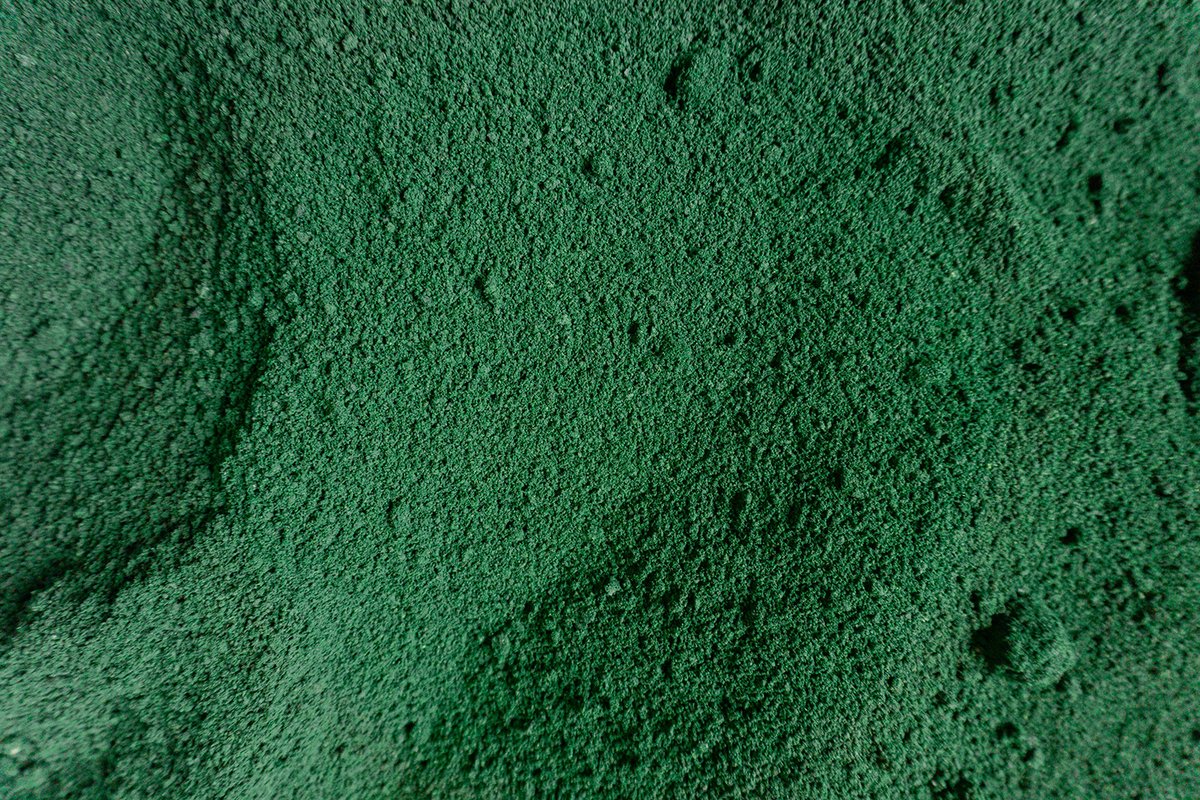

(Article continues below the image)

By allowing evergreen grass and clover to grow in fields, we can start designing an agricultural landscape based on natural-science principles of the best use of resources.

In a circular mindset and from a climate perspective, it is about having as long a growth season and as many green plants as possible. This creates photosynthesis, and it binds carbon from the atmosphere in the biomass.

"Photosynthesis is the only significant negative greenhouse gas emission we have at the moment, and it has a major impact on the carbon balance. That's why we have to get as much of it as possible. And from there we can begin to solve the climate challenge technologically. More green crops will be a revolution in agricultural production, because they are clearly the most optimal for the climate, the environment and nature, but up to now there has been no market for green crops other than as cattle fodder,” says the professor.

- READ MORE: Green protein – what do we know, and where are the challenges? (in Danish)

Total reorganisation of food production

The vast majority of the yellow crops grown today are also used for animal feed, and only a little goes to other uses such as human consumption. Residues such as straw are used for feed, litter and fuel and biogas production.

The perspectives for green crops are somewhat different.

Firstly, green crops can produce far more biomass per hectare of farmland than yellow crops. They are also far more resilient to diseases and bind more carbon and nitrogen.

The green biomass can supply energy in biogas plants, and via biorefining can be converted into protein concentrates, chemicals, bioplastics, building materials, green fuels, clothing textiles, pharmaceutical products and much more.

- READ MORE: She makes clothes out of grass

Researchers at Aarhus University can already extract white protein from grass at laboratory scale – protein that can be used for human foods.

"There’s no commercial production of grass protein for food yet, but at pilot scale we’ve shown that we can extract protein from grass and use it for food. The biggest hurdle is to develop high-protein products that match human sensory taste buds, but we’re working on that, and we also believe that it can become a profitable business in the future. At the moment, we’re researching into understanding the molecular interactions between proteins and other components of foliage plants, so that we can optimise taste and functional properties of the extracted protein that help provide structure for foods," says Associate Professor Trine Kastrup Dalsgaard from the Department of Food Science.

(Article continues below the image)

If we go one step further and couple with further bio- and chemical engineering processes, such as electrolysis, we get into the whole area of Power-to-X and the electrification of society. This means that green biomass from agriculture could be a major player in a wide range of industries that today are based almost exclusively on fossil raw materials.

"The biodiversity crisis, pollution of nature and the environment as well as the climate crisis are massive issues where many of the solutions can be found using the same approach, i.e. far better and more efficient production of biomass and a multitude of technologies that can convert biomass into the products that society is looking for now and in the future. It entails a total and complete reorganisation of the way we produce food, and it has far-reaching consequences for carbon-based manufacturing industries," says Professor Lars DM Ottosen, head of the Department of Biological and Chemical Engineering.

He continues:

"We've come to a point when we have to rethink everything. Right now agriculture has a chance to take the lead and become the driving force behind the entire green transition. Clearly, this requires a great deal of development, primarily relating to the total reorganisation of our food production, but if we do so the possibilities are colossal."

- READ MORE: Grass can replace plastic as packaging

Unique possibilities

Lars DM Ottosen believes that the main difference in the agriculture of the future will be far less livestock. Instead, meat and other animal products will be replaced by plant-based and cell-based technologies.

"Generally, nothing can measure up to a cell-based approach to food production. The technology doesn’t pollute, and there are only moderate losses. We can produce the same amount of food with a significantly reduced feed input compared to that demanded by large livestock, and coupled with green crops, this will mean that you can produce far more food on the basis of much less farmland. This opens up for more nature in many of the areas that are currently used for agriculture, and with far more environmentally friendly biomass production, we’ll have good opportunities to improve biodiversity and the environmental state of nature," he says and adds:

"However, the transition of our biomass and food production requires a technological revolution in line with the transition of our energy systems, and this must not be underestimated."

- Read more about cultured meat here

(Article continues below the image)

Jette Feveile Young is an associate professor at the Department of Food Science and researches both meat quality and a cell-based approach to meat production. She believes there is a huge potential in producing meat in bioreactors, but this does not necessarily mean that all traditional meat production will therefore be phased out:

"Instead, think of getting one cow to become 1.2 cows," she says and continues:

"Here in Denmark, we’re rather good at producing meat and agricultural products, and we should exploit this. There’s no way around it, no matter how good we are at traditional meat production, change is mandatory given the climate and biodiversity crisis. Therefore, we could incorporate the cell-based approach, whereby muscle cells from animals are cultivated for meat in bioreactors, as an effective contribution to an overall circular production. In this context, Denmark could be a perfect pioneer country, because we already have everything we need to get the process up and running."

The future for Danish agriculture

Research at Foulum has already come a long way.

The first farm site for biorefining grass was taken into use in 2020 by Kristian Lundgaard-Karlshøj, a farmer at Ausumgaard near Struer, and more and more farmers are looking at the possibilities in a new Danish export enterprise that literally is green.

"We have some important goals to reach by 2030 and even bigger goals for 2050, and we will have to work with companies and enterprising farmers to reach these. The possibilities at Foulum are unique, and the collaboration between engineering science, agroecology and food and animal research opens up for many exciting new areas to take us even further with these technologies. An exciting future lays ahead for Danish agriculture," says Professor Uffe Jørgensen.

Contact

Professor Uffe Jørgensen

Department of Agroecology

uffe.jorgensen@agro.au.dk

Tel.: +45 21337831

Professor, head of department Lars DM Ottosen

Department of Biological and Chemical Engineering

ldmo@bce.au.dk

Tel.: +45 51371671